"Do you think the way you were treated after your stroke was because of race?"

- Diane M. Barnes, M.D.

- Apr 29, 2018

- 6 min read

Another audience question from talkback following performance of My Stroke of Luck.

The deficiencies in my treatment, both at discharge and in follow up, were more likely related to my being a physician than race. Although there are serious disparities in healthcare delivery, both for women and minorities particularly African-American, I do not believe either were major factors in my case.

As soon as I presented to the hospital, my care was attentive and expedited. Even in retrospect, my hospital care was flawless: attentive, and meticulous.

More likely, the fact that I was a physician and employee of the hospital system where I sought treatment where limiting factors. Hospital power dynamics (deference to doctors) and HIPAA (health Insurance Portability and Accountability act) policy concerns likely inhibited full assessment of my case, including sharing the kind details essential to personalizing care by non physicians.

(Although HIPAA didn’t stop my former boss from calling the doctors taking care of me at Kaiser Redwood City to find out –without my permission- details of my case, which they discussed -again, without my permission, both violations. He phoned me one of my first weeks home to tell me based on what he’d learned, not to bother trying to get back to work!!!)

But being a doctor may have worked to my advantage in the neurologic ICU. My only longer than three second memory from that stay: I awake in a large room lit yellow blue, beeps and whooshes, murmuring voices, a large, white, naked backside at the end of my bed. I blink. It’s balding, stocky. A man in a hospital gown that barely covers his sides. Holding an IV pole. Who is this? I scream. He turns around. Where am I? Why is a naked man in my room? I bolt out of bed, run for who knows where. Did I have an IV I yanked out? Was my backside also bare? No idea. “Hey, you’re not supposed to get up. Get back in bed.” My next memory: I wake up in a dark, quiet, single room, where I remain until discharge.

The failures in my case began with discharge. But part of the problem was that my internist worked in Oakland, I was hospitalized in Redwood City, I was a Kaiser San Rafael area resident and employee and Kaiser Vallejo was the rehab center for my area. At that time, the in and outpatient medical records were not fully electronically integrated, so my various records were not readily available. No one could get a history from me after the emergency room, so the social and personal histories, which would have included information about my children and support systems, were unavailable to the discharge planner.

In a previous newsletter (see blog post of 1/28/18), I covered the Activities of Daily Life (ADL= ability to walk, feed and toilet oneself) Scale that determines whether one goes to rehab, is prescribed home assistance or goes home unassisted after discharge. Though I certainly needed more than I was offered or given, my treatment met the prevailing standard of care.

I have also mentioned, for optimal post stroke recovery, one’s care should be managed by a physiatrist, a physician who specializes in physical medicine and rehabilitation. Though there were fewer physiatrists in the system thirteen years ago when I had my stroke, the different geographic locations of my care team probably contributed to that fall through the cracks. My internist, whom I love, arranged for follow up assessments after I was home, when she would have received the discharge summary from Redwood City, then arranged services.

How were you treated by other medical professionals?

I remember my occupational therapist with great fondness. She arrives, clipboard and pen in hand. Kind eyes. Gentle. Non judgmental. Caring.

“Just go about your life as if I’m not here,” she says. “I’ll observe, make some notes and offer you some strategies for coping.”

Suddenly I’m, standing in the middle of the living room. “What am I doing here?” I’m thinking.

“Looks like you forgot what you doing,” she says. “You said you were thirsty. You got up to get a glass of water but you forgot. What you’re doing now is practicing forgetting. You need to practice remembering. Go back to your room and sit down. Good. From now on, before you move, repeat your intention until it’s done. So, what is it you want now?”

”A glass of water.”

"Now what do you need to do?”

”Standup.” I stand.

“No. Sit back down. Repeat ‘glass of water.’ Then stand up.”

“Glass of water. Glass of water.”

”Good. Now what?”

”Walk to the kitchen.”

”Yes, repeat glass of water, glass of water while you walk into the kitchen. And you need to keep repeating it while you do the next steps, until you have a filled glass of water. What is the next step?

You get the idea.

“Good. Now you’re practicing remembering!”

The speech pathologist was also wonderful.

But the Chief of Neurology was not. I don’t remember exactly how many months after my stroke it was before I saw him. It was long enough that I was speaking correctly again, and that I had enough understanding and memory to have begun to grasp the extent of my memory, cognitive and spatial awareness losses. I did my best to explain them to him.

“There’s nothing you’re telling me that isn’t true of a lot of other people your age.”

“But they were not true of me the day before my stroke. These are sudden changes from the stroke.”

“Well, you’d better get used to it. You’re brain damaged now.” He shrugged and smiled. I will never forget that look, which, though definitely colored by ageism, might also have been tinged with sexism and racism. I fired him.

The difficult challenge was having to direct my own recovery, search out helpful clinicians and services, though the guidance of my colleague, Steve, who himself had overcome a traumatic brain injury, was a God send. And I found therapists and others who listened, were open hearted and most importantly, encouraging and supportive about how much function I might recover.

As I have mentioned, after initial expressions of sympathy, my colleagues mostly distanced themselves. Sad, but not surprising. Something has to help those of us in medicine cope with the degree of vulnerability, suffering, disease, death and loss we see on a daily basis. From the moment we meet our naked cadavers first year medical school through training, we learn to shield our feelings, to separate them and us. So an injured colleague is a threat to that separation, a way too vivid reminder that there but for fortune.

The colleague other than Steve who was the most supportive, Adam, said it with compassion (I heard his voice mail way later):

“OMG! I just read your CT scan. I can’t believe it. You eat right, you’re slim, you exercise. If this could happen to you, what about the rest of us?” He saw himself and reached out. Others did not.

But many were unaware of my stroke. Partially, I was a private person, a busy working professional and single mother, and my network at the hospital, was more collegial than intimate. But partially, that’s how the hospital (and many workplaces) work. The priority is on getting the job done, not reaching out to those who for whatever reason are no longer working. After an early run through of my show for a group that included many physicians, I heard a lot of sentiment that we as a group, and the hospital as a work place, to do a better job of reaching out to impaired colleagues. Sadly, this is not a universal sentiment. After I retired, the Physician in Chief disbanded the Impaired Physicians Support Group; many of its members left the practice.

How would you have liked to be treated by your colleagues?

Too much to fit here; this I’ll address in another newsletter about getting back to work.

How would you have liked to be treated by medical personnel?

As the unique individual I was and am. Hear what I am saying! Don’t compare me or tell me about other people. Don’t tell me I’m lucky, it could have been worse. That trivializes my experience. I am keenly aware of what I have lost. That’s my yardstick.

Interestingly, this is an issue in assessing brain injury. Almost no one has baseline studies to document their pre injury functioning. So the impairment, other than one’s personal feelings or achievements that indicate indirectly a level of functioning, can be difficult to objectively assess. Neuropsychological testing, of course, is helpful, but for any individual, without pre and post testing, no way to know. (Great that now sports teams are beginning to do initial assessments to provide a baseline.)

I’ll wrap this one here, with thanks for all your questions. If you have other questions, just shoot me a line, I'll try to address them in an upcoming newsletter.

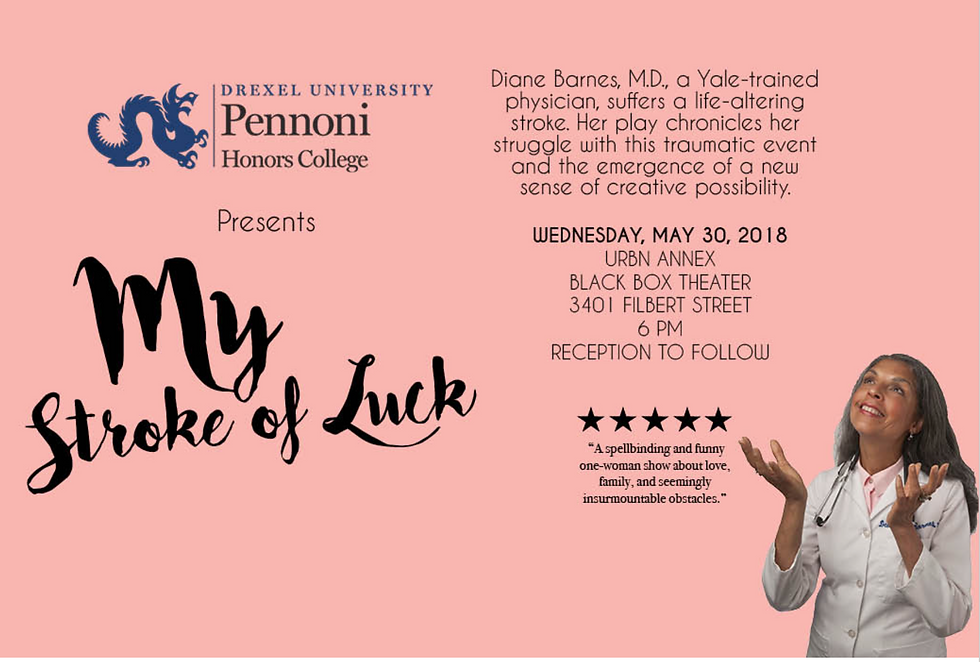

NEXT OPEN PERFORMANCE:

This event is free and open to the public with a reception to follow the performance, but please RSVP here. Presented by Pennoni Honors College with venue collaboration from Westphal College of Media Arts & Design. For more information, contact Brian Kantorek, Assistant Director of Marketing & Media, Pennoni Honors College (briank@drexel.edu or 215-895-6201).